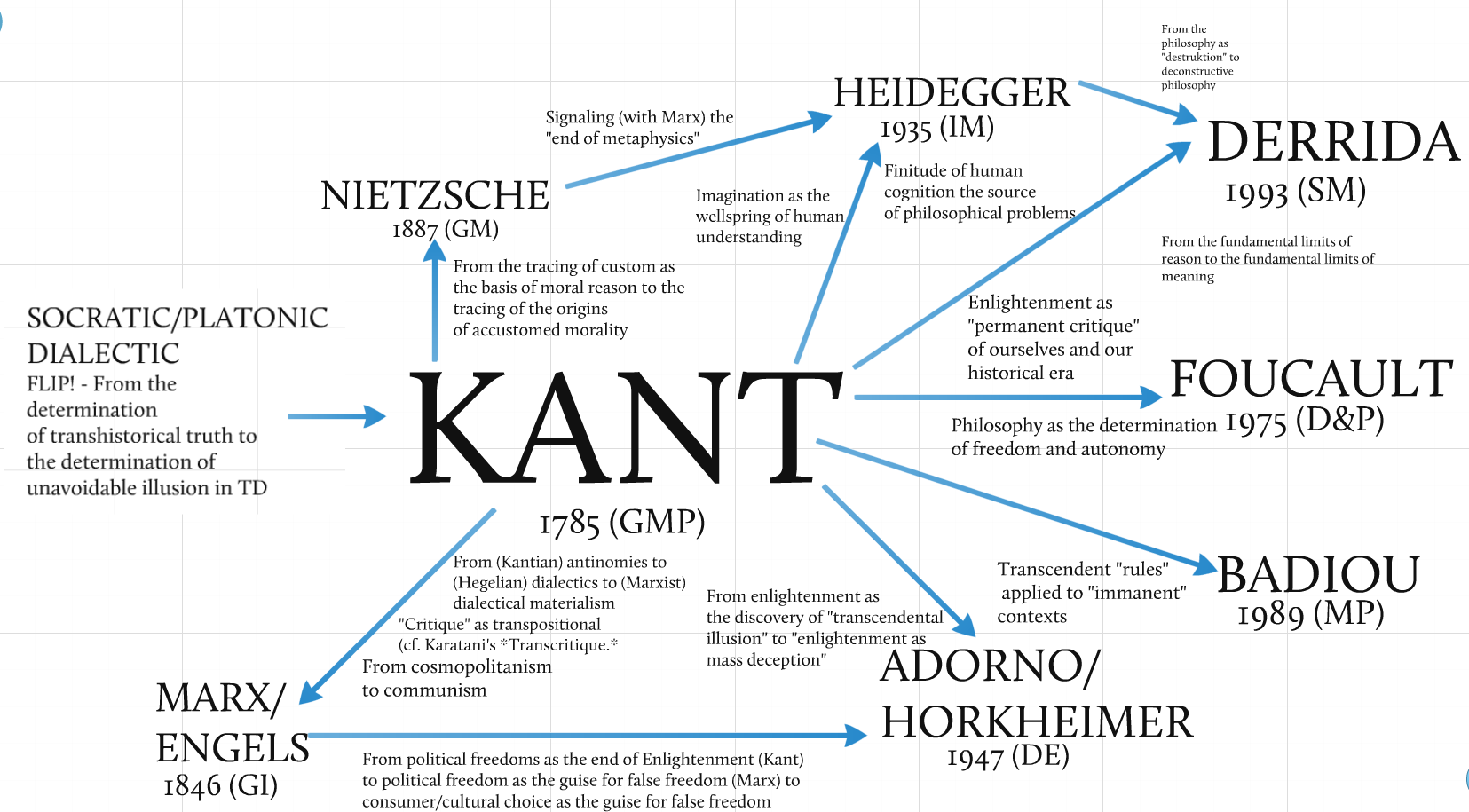

In his “Dialectics of the Fable” (2000), Alain Badiou discusses a series of films, Cube(1997), The Matrix (1999) and David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999), as philosophical machines. These are films that, in Badiou’s estimation, both reflect upon and in a sense encapsulate a set of “problems” – what we might call disturbances in the psycho-social fabric of the medium – disturbances that not only point to a crisis, but are themselves critical. Concerned with the status of the “Real,” these films are necessarily both self-reflexive and projective in a way that subverts the “mentally divergent” dualism of illusion and reality (viz the madhouse scene in Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995)) by folding the transcendental loop back on itself – from a dialectics of the “fable” to the entropic spiral of the “image”: a force-feedback that produces a breakdown between the fantasy of the Real (as simulacrum) and the simulacral character of the fantasy itself (its filmic bipolarity). “What is a subject who is unable to assure itself,” Badiou asks, “of an objective existence?” Cronenberg’s response – the dreamlike looping recursive structure of eXistenz (faint echoes of Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)) – “isn’t assuring,” Badiou argues. “It seems to point towards a subject of the unconscious, a monstrous, violent, sexual projection of an Ego revealed by the gamelike effacement of objectivity.” This is mirrored in the regressive structure of the film itself, as “pursuit,” “quest,” “escape” through the “wilderness and perils of a world of the seeming…”.

Badiou regards this type of filmmaking as “phenomenological,” to the extent it is concerned with the immanence of a certain reality. Like Cronenberg’s earlier film, Videodrome (1983), eXistenZ is first situated within a recognisably realist framework. This is a regular feature of Cronenberg’s work and, in a way, that of Gilliam’s and David Lynch also (from Brazil (1985) to Inland Empire (2006)). “Ordinary, heterogeneous elements” – such as machines and biology – are frequently the chosen agents by which realist conventions are dismantled by each of these directors, exposing what we might call the ideological structure of cinematic realism (something Lynch especially has made a focal point). It is as though realism itself is turned against the belief that the world is in some sense construed or even fabricated with a mindful purpose – in place of a void. In place of this, we are given a world structured by violent enigmas.

In a series of essays on Cronenberg, Burroughs and Deleuze, Cengiz Erdem argues that, “in Cronenberg’s films we see the theme of machines replacing humans in the process of being replaced by the theme of humans connected to machines, or machines as extensions of humans providing them with another realm beyond and yet still within the material world” where the “psychic and the material” recursively feed back into each other:

“In eXistenZ, for instance, we have seen how the game-pod is plugged into the subject’s spine through a bio-port and becomes an extension of the body. In Naked Lunch the typewriter becomes Lee’s extension. In Burroughs the obsession was still with the machine taking over the body. In Cronenberg’s adaptation of Burroughs the obsession is with body and machine acting upon one another.”

The point is, however, that in Burroughs and Cronenberg it is really a question of the prosthetic character of the body as extension of technology: the body-as-such exists no more than “the machine” exists, or “the mind” exists. In The Perfect Crime, Jean Baudrillard makes the salient observation that “we play with death in technology as other cultures did in sacrifice” (“If I can see the world after the point of my own [fantasmatic/proxy] disappearance, that means I am immortal”). Machine-death or, as Freud says, the “death drive” situates that counter-intuitive impulse (existence-as-entropy) that propels the body towards its fantasmatic, technological other, of which it is in fact already the mirror image – this body which is already a simulacrum of its own corporeality. For Baudrillard it isn’t a question, however, of asserting “that the real does or does not exist – a ludicrous proposition which well expresses what that reality means to us: a tautological hallucination… There is merely a movement of the exacerbation of reality towards paroxysm, where it involutes of its own accord and implodes leaving no trace, not even the sign of its end. For the body of the real was never recovered.” For Cronenberg, Interzone becomes an allegory of the “spectacle” in its domination of all aspects of social consciousness, which in turn is merely a reification of its unconscious existence. As Debord famously puts it: “For one to whom the real world becomes real images, mere images are transformed into real beings – tangible figments which are the efficient motor of trancelike behaviour…” Hence:

“The spectator’s alienation from and submission to the contemplated object (which is the outcome of his unthinking activity) works like this: the more he contemplates, the less he lives; the more readily he recognises his own needs in the images of need proposed by the dominant system, the less he understands his own existence and his own desires. The spectacle’s externality with respect to the acting subject is demonstrated by the fact that the individual’s own actions are no longer his own, but rather those of someone else who represents them to him. The spectator feels at home nowhere, for the spectacle is everywhere.”

In an important corollary, which comes to characterise the sense of powerless effected by the spectacular character of even the most fundamental human interactions in many of Cronenberg’s films, Debord notes: “The spectacle is by definition immune to human activity, inaccessible to any projected review or correction. It is the opposite of dialogue. Whenever representation takes on an independent existence, the spectacle re-establishes its rule.” This is nowhere more explicit than in Cronenberg’s Videodrome.

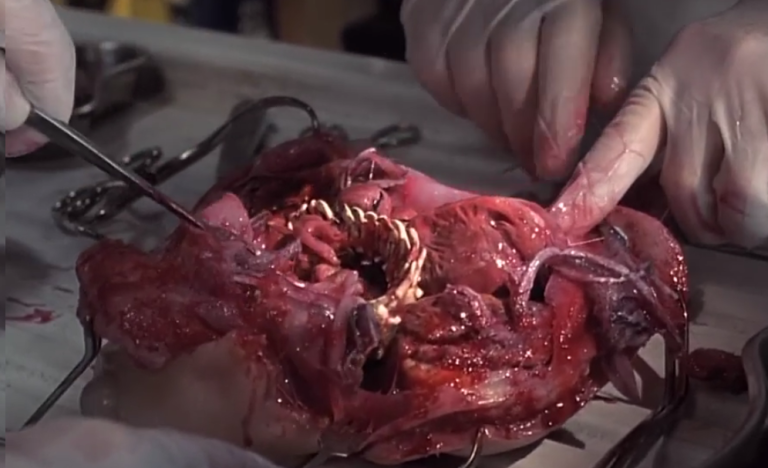

David Cronenberg, Videodrome (1983)

David Cronenberg, Videodrome (1983)

Produced in 1983, Videodrome was described by Andy Warhol as “A Clockwork Orange of the ’80s.” The film stars James Woods as Max Renn (director of a small-time cable network, Civic TV), Debbie Harry as Nicki Brand (a local radio talkback personality with whom he enters into an hallucinatory, sadomasochistic “affair”), and Jack Creley (Professor Brian O’Blivion, a Marshall McLuhan clone). It is in large part an investigation into the ideological coding of reality and of individual behaviour mediated by the omniprescence of TV and video culture, in which the idea of an image is inextricable from that of a signal or command (medium and message). Renn, bored with Civic TV’s regular slate of exploitation and porn, complains that “It’s too soft. There’s something too… soft about it. I’m looking for something that will break through. Something tough.” His tech assistant, Harlan, meanwhile reports that he’s locked onto a pirate satellite broadcast, called Videodrome which features torture and snuff unchangingly played out in a clay-walled dungeon.

Videodrome, however, turns out to be a weaponised image-as-signal emanating from a mysterious type of influencing machine that assumes control of Renn’s consciousness, making him into its agent in a secret war being played out between O’Blivion’s “Cathode Ray Mission” and its nemesis, Convex’s “Spectacular Optical.” In a key scene, O’Blivion describes the Videodrome programme as the arena of an evolutionary struggle in the production of the “New Flesh,” while for Convex it’s an apparatus of (moral-fundamentalist) social control: in part evoking William Gibson’s “Matrix”; in part, something between Jeremy Bentham panoptical apparatus of psycho-technical discipline and punishment and Debord’s Society of the Spectacle. O’Blivion, Videodrome’s “prophet,” is revealed to be already dead, while maintaining a virtual existence as a VHS archive. O’Blivion’s “death” is recoded as “a refusal to appear except on television”: “The television screen has become the retina of the mind’s eye,” he says during one broadcast. “For that reason, I refuse to appear except on television. O’Blivion is not the name I was born with. It’s my television name. Soon, all of us will have special names, names designed to cause the cathode-ray tube to resonate.”

O’Blivion prophesies a future in which existence itself will function as a type of autonomous symptom of TV reality, like his own brain tumour, which he considers not to be the symptom of a disease but rather a new organ of perception:

“…massive doses of Videodrome signal will ultimately create a new outgrowth of the human brain, which will produce and control hallucination to the point that it will change human reality…”

The Real will no longer be the beyond of the virtual, or something masked or distorted by the virtual, but an outgrowth of the virtual itself – a hyperreal, in Baudrillard’s words (“Total transformation,” as Nikki Brand tells Renn. “To become the new flesh, you have to kill the old flesh”: “Projecting ourselves,” so Baudrillard says, “into a fictive, random world for which there is no other motive than this violent abreaction to ourselves.”) As in Gilliam’s Brazil, it’s not a question of reality being perverted but of perversion as social regulation (the real obscenity in Videodrome is the system of control which propagates itself by way of a viral snuff pornography). In a type of Freudian gesture more explicitly (yet less exactly) examined in Cronenberg’s 2011 film A Dangerous Method, we are made to witness the invasion of the “Real” into the fantasy of regulated desire: the conventional relation between virtuality and reality is not merely inverted, it is abolished. In The Sublime Object of Ideology Žižek writes:

When Lacan says that the last support of what we call “reality” is a fantasy, this is definitely not to be understood in the sense of “life is just a dream,” “what we call reality is just an illusion,” and so forth… Such a generalised illusion is impossible… The Lacanian thesis is, on the contrary, that there is always a kernel, a leftover which persists and cannot be reduced to a universal play of illusory mirroring. The difference between Lacan and “naïve realism” is that for Lacan, the only point at which we approach this hard kernel of the Real is indeed the dream. When we awaken into reality after a dream, we usually say to ourselves “it was just a dream,” thereby blinding ourselves to the fact that in our everyday, wakening reality we are nothing but a consciousness of this dream. It was only in the dream that we approached the fantasy-framework which determines our activity, our mode of acting in reality itself.

In Videodrome this simulacral existence is more than simply an extension of the “virtual into the real,” in which the body functions as a complex of symptoms operated by the automaton within: the individual experiences himself to be this alien video-body, which it both materialises in the flesh and – so to speak – cannibalises. This tumorous “outgrowth” is both a reification and the violent abolition of the mind-body dualism, by which consciousness itself presents as the extruded physical body (“the new flesh”) of an autonomous phantasm which in fact programmes it (what Žižek calls the nothing of transcended fantasy). “Fantasy,” as Žižek says, “is a basic scenario filling out the empty space of a fundamental impossibility, a screen masking a void…” The object of Renn’s fantasy (Nikki Brand) is shown to be something ultimately alien, originating in some unacknowledged or secret place (not the Videodrome arena/torture chamber, but coded inside the video signal itself, as the very possibility of the “message”). “Fantasy,” Žižek concludes, “conceals the fact that the Other, the symbolic order, is structured around some traumatic impossibility, around something which cannot be symbolised.” We are then left with the question: “What happens with desire after we ‘traverse’ fantasy?” The answer offered by Cronenberg in the culminating scenes of Videodrome when Renn shoots himself in the head (first “on TV,” then “in real life”) is, for Žižek, “ultimately the death drive”: “‘beyond fantasy’ there is no yearning or some kindred sublime phenomenon, ‘beyond fantasy’” we find only this mindless dissolution into the objectified “Real.”

A game pod being operated on in David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999)

In his 1981 essay, “Simulacra and Simulations,” Baudrillard – who was at pains to distinguish virtuality from Debord’s notion of the “spectacle” (on the basis that the spectacle “still left room open for critical consciousness and demystification” while virtuality (as unconditional realisation) is “irrevocable” ) – outlines the following successive phases of the “image” in the genealogy of reality’s disappearance:

1. it is the reflection of a basic reality

2. it masks and perverts a basic reality

3. it masks the absence of a basic reality

4. it bears no relation to any basic reality whatsoever: it is its own pure simulacrum.

These are the basic evolutionary steps of what Baudrillard terms the hyperreal, in which “we are no longer spectators, but actors in the performance, and actors increasingly integrated into the course of the performance… We are, in fact, beyond all dis-alienation.” There is no escape from this “desert of the real.” Unlike the Wachowskis’s The Matrix, with its red pill and blue pill – in which both the reality of the illusion and a fundamental reality behind the illusion are not only in-and-of-themselves real – in Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999) there’s no escape: no other constitutive reality upon which the socalled simulacral world is founded and with respect to which a critical consciousness may be maintained (other than as paranoia). Like in the ancient Chinese proverb, it’s simulacra all the way down.

In many respects eXistenZ is a reprise of Videodrome, where interactive gaming has taken the place of video. The plot involves three simple elements, which are recombined in varying permutations to produce the film’s action and narrative structure. In this way, Cronenberg’s film borrows from von Neumann and Morgenstern’s seminal Theory of Games and Economic Behaviour, a study of probability, strategy and hypothesis, and from an array of “possible worlds” theories. These three elements are represented by two competing games consol manufacturers – Antenna Research and Cortical Systematics – and an anti-gaming movement of “realists” opposed to its “deformation” of reality. Throughout the film it’s difficult to keep track of which forces are represented by which characters, and as the narrative delves into deeper game-levels the logic dictating actions becomes more dreamlike and “probabilistic” rather than “purposive” in any straightforward sense. The film uses varying strategies of illusionism to entice the viewer, but at the end we – like the film’s protagonists – are left suspended in uncertainty as to what constitutes the “game” and what constitutes “reality,” or whether the real itself is constituted as an extension of the game; that there is, in effect, no escape.

Cronenberg advances this point by obscuring from the outset any clear distinction between the organic and the technological, the real and the artificial. Gamers jack into their consoles through “bio ports,” via which the “game pod” is connected by an “UmbyCord” directly with the player’s nervous system. The “pod” operates as a type of prosthetic consciousness; an externalised representation of subjective “agency” or ego. Players’ actions are dictated by the characters they play and the situations in which they find themselves rather than autonomously. The game itself is a type of desiring machine, producing a complex of symptoms in which the antagonistic/destructive impulses represented by the film’s three elements (the two competing fantasy systems and the “real”) are coded, distorted, concealed, displaced. It would be easy here to find analogies to Freud’s schema of the id, ego and superego – and the confusion between a neurotic complex (the breakdown in the ego’s relation to the interior drives, or id) and psychosis (the breakdown in its relation to an external reality). With reality virtualised, the two conditions become synonymous, and the only basic reality open to experience is that of the paranoiac.

We are left with the dilemma: how is a critical action possible where there is nothing upon which or against which criticism can be directed? What does it mean to be a “realist” within the framework of an all-pervasive virtuality? Of a “reality” that is always provisional, contingent, tactical? Cronenberg appears to suggest that it is rather the compulsively repetitive, permutative cybernetic character of this “virtual reality” – characterised by a certain return of the repressed – that offers the only grounds. A form of criticism as perturbation – the fantasy of the real traversed by disturbances that arise from the incommensurability of the so-called real itself, which is (nothing) but an image. Or as McKenzie Wark writes in Gamer Theory:

Ever get the feeling you’re playing some vast and useless game whose goal you don’t know and whose rules you can’t remember? Ever get the fierce desire to quit, to resign, to forfeit, only to discover there’s no umpire, no referee, no regulator to whom you can announce your capitulation? Ever get the vague dread that while you have no choice but to play the game, you can’t win it, can’t know the score, or who keeps it? Ever suspect that you don’t even know who your real opponent might be? … Welcome to gamespace.

Rosanna Arquette in Crash (2004)

Throughout his filmography, Cronenberg’s “cinema of perversion” can be seen to explore the way in which the viewer’s gaze is implicated in that of a film psychology that traverses the limits of the “normal” – exposing the foundations of normality in perversion, rather than presenting the perverse as a deviation from a norm, centred particularly in the relation of the organic body to the invasive “technology” of the virus or machine. In J.G. Ballard’s 1973 novel Crash, the automotive “body” and the culture obsessed with it represents a “perversion” which is at once the rule, and its exception. The novel epitomised, according to Simon Sellars, “Ballard’s ‘death of affect’ theories… The media landscape, with its aestheticisation of violence, is the novel’s main character. The car, the first and still most recognisable symbol of mass production, provides the eternal metaphor.” The plot has the “superficiality” and recursive monomania of a porno film:

It tells the story of the narrator, “James Ballard,” the “hoodlum scientist” Vaughan, and a supporting cast of curiously one-dimensional characters as they follow their peculiar obsessions along the hyperreal motorways of England. Tuned to police radios, they descend on the scenes of car crashes, depositing their semen and vaginal mucus on torn flesh and twisted metal. Ultimately Vaughan desires ‘a union of semen and engine coolant,’ splattered in world-wide “autogeddon.”

We are confronted with a general psychopathology, in fact, hinging upon a form of barely sublimated mass hysteria (consider the ending of Cronenberg’s 1975 film Shiversfor an immediate analogy). Like the serial, obsessive images in Warhol’s disaster series, in which a media-saturated spectatorship is confronted with the banality of its own pornographic fascination with death – a fascination exposed as an obscenity, because otherwise sublimated or objectified onto external agents.

In Cronenberg’s 2004 film adaptation, the external agent is the character named Vaughan, a car crash fetishist. Vaughan comes to articulate and even channel the formerly unacknowledged desires of the film’s other characters, principally James Ballard (James Spader) and Dr Helen Remington (Holly Hunter), who are involved in a head-on collision. While the trauma of the crash acts as a catalyst, it is Vaughan who appears as the embodiment of the characters’ unconscious drives – he is both enactor and re-enactor, anticipating and recycling a kind of automotive eroticism: he narrates the characters’ unconscious desires to them, just as he narrates the details of the famous car-crashes he stages for an underground audience.

It’s no accident that the word drive evokes an association with Freud’s exploration of the unconscious entanglement of the pleasure principle and death. Driving, for Cronenberg, becomes more than simply a metaphor, it encompasses an entire ontological condition. The car, the auto-mobile, becomes an analogue to the Cartesian interior God, the Ego-operator, whose archaic form is realised in the figure of Vaughan. The supposedly organic drives are given a technological armature; bodies and machines, just as in Descartes, mesh: the desiring subject is wired into an entire system of flows and cataclysmic discontinuities – of which it is conscious in only the mesmerised way of Ballard and his wife Catherine during the opening of the film as they stare down at the freeway from their highrise apartment building (mesmerised in their act of contemplation which becomes, in turn, an act of detached copulation). The scene describes a disconnection and ennui which masks a slumbering libidinal force that only requires the “crash” in order to be awoken (which is to say, the impulse towards death rendered as a state of consciousness).

Up until this point the characters’ lives appear to have been dreamlike; the “crash” exposes a potent “hidden reality.” Ballard’s novel, on which the film is based, begins with Vaughan’s death, marking a closed circuit – the other characters, thus aroused from their libidinal ennui, no longer require Vaughan’s deus ex machina – they have learned to become agents of desire in their own right, to “love their symptom,” as Žižek says. Ballard’s prose achieves an almost erotic intensity:

“Vaughan died yesterday in his last car-crash. During our friendship he had rehearsed his death in many crashes, but this was his only true accident. Driven on a collision course towards the limousine of the film actress, his car jumped the rails of the London Airport flyover and plunged through the roof of a bus filled with airline passengers. The crushed bodies of package tourists, like a haemorrhage of the sun, still lay across the vinyl seats when I pushed my way through the police engineers an hour later. Holding the arm of her chauffeur, the film actress Elizabeth Taylor, with whom Vaughan had dreamed of dying for so many months, stood alone under the revolving ambulance lights. As I knelt over Vaughan’s body she placed a gloved hand to her throat.”

This is a familiar theme in Cronenberg’s films – in which the protagonists usually undergo a transformative journey culminating in some sort of transcendence. The model could easily be Dante, with Vaughan as the Virgil-figure, the guide through Hell and Purgatory. As in Videodrome and Naked Lunch, the journey is already a kind of repetition in which the drama assumes the form of a “return of the repressed.” In Videodrome this is achieved through the idea of playback, in Naked Lunch through the displacement of the guilty conscience (Joan Lee’s accidental death), in Crash through the dissolution of “event” into “re-enactment” and “rehearsal.” The mode is inherently sexual; the driven intensity tending towards exponential. Death, the ultimate “real,” represents something verging upon an erotic sublime, or the kind we encounter in the writings of Georges Bataille: the consummation of the impossible. The automobile, that ubiquitous symbol of “potency” in a consumer society driven by petro-dollars, becomes the locus of all sexual gratification.

Desire in Cronenberg is always linked to some sort of otherness: the video screen – some archaic, alien insect-form of the unconscious – or machines. As in Freud, the organic life-processes – so-called instincts – are re-figured as a form of overcoded mechanism: a complex assemblage the body is barely able to mask, and which becomes increasingly exposed on its surface: literally, in Crash, in the form of surgical prostheses and tattoos, anticipating a type of “ideal marriage” of body and machine – “the reshaping of the human body,” as Vaughan says, “by modern technology.” Or as Ballard writes:

In his vision of a car-crash with the actress, Vaughan was obsessed by many wounds and impacts – by the dying chromium and collapsing bulkheads of their two cars meeting head-on in complex collisions endlessly repeated in slow-motion films, by the identical wounds inflicted on their bodies, by the image of windshield glass frosting around her face as she broke its tinted surface like a death-born Aphrodite, by the compound fractures of their thighs impacted against their handbreak mountings, and above all by the wounds to their genitalia, her uterus pierced by the heraldic beak of the manufacturer’s medallion, his semen emptying across the luminescent dials that registered for ever the last temperature and fuel levels of the engine.

Michael Fassbender as Jung & Keira Knightley as Sabina Spielrein in A Dangerous Method (2011)

4. “Sometimes you have to do something unforgivable just to be able to go on living.” So says Carl Jung to his former patient, Sabina Spielrein, at the end of Cronenberg’s 2011 investigation of hysteria, sexual perversion, freedom, orthodoxy, infidelity and the Oedipalised power-relation at the heart of the emergent psychoanalytic movement (and at the heart of cinema), entitled A Dangerous Method.

It’s notable that for his only direct engagement with the Freudian science of the unconscious Cronenberg elected to shoot this film (based on the 1993 book A Most Dangerous Method: The Story of Jung, Freud and Sabina Spielrein, by John Kerr) as a more or less conventional period drama. Cronenberg exploits the period genre to merge naturalism and a certain mannerism, evident in the costumes, settings and dialogue. In tandem with the logic of psychoanalysis, the film examines the constitution of normality. To this end, the character of the young hysteric, Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley) – who is referred to Jung (Michael Fassbender) for treatment by the founder of psychoanalysis, Freud (Viggo Morgensen) – represents a paradoxical figure. Her illness manifests itself in a series of hysterical symptoms that cause her behaviour to depart dramatically from what would be considered ordinary. Spielrein’s aberrant behaviour nevertheless corresponds to a certain type (the actual behaviour of an hysteric) – so that what stands out as most aberrant in the film is achieved precisely by naturalism.

We can recognise an automatic distinction here with the exaggerated mannerism and general “weirdness” of Naked Lunch. Cronenberg seeks to achieve an effect of dislocation without resorting to a phantasmagoria. Alongside the “dangerous method” of psychoanalysis, it’s as if Cronenberg were seeking to draw our attention to the likewise “dangerous method” of realism itself, behind whose façade all that’s aberrant is normalised. It’s as if the “method acting” Cronenberg requires of his ensemble in this costume theatre is itself a kind of symptom – like the scene in which Spielrein watches herself in the mirror, hands strapped to the bed-head, while Jung whips her with his belt: a mimesis in which the libidinal drama unfolds in kind of entropic loop, perpetually replayed with all the sincerity and intensity the “method” is programmed to avail itself of, and whose climax is merely the glitch, the freeze-frame, before the loop feeds back to begin again. This hysterical image is also an image of distanciation in which libido is never “experienced” but merely performed, costumed, symptomatised – beyond, we are told, is mere anarchism (embodied here in the person of Vincent Cassel) – since it is the illness itself that is “the method.”

We encounter this idea repeatedly with regard to the theme of “repression,” which the pervasively sexual character of Freud’s theories facilitates. Jung, the married protestant Swiss doctor, is presented as a figure of rectitude, propriety, and consequently of guilt, anxiety and dishonesty. Spielrein, on the other hand, is presented as a figure of libidinal excess whose sexuality has been channelled, by her disciplinarian father, into a perversion of which she is first ashamed and later through which she finds release: that is, sexual arousal and gratification achieved solely by flagellation, or its metonymic representation (Jung beating the dust out of her coat; her own reflection in a mirror; her father’s hand – which may also be the “dead hand” of a certain realism, the anaesthesia of symbolic depiction, etc.).

By all accounts, both Jung and Freud themselves experienced breakdowns, both of which are touched upon in the film. The implication being that “illness” is itself part of the “cure”; that what is normal can only be arrived at by way of “deviation”; and that the cost of accomplishing the former cannot be at the expense of the latter. The suppression of the “abnormal” results only in illness. The implication here is that normality itself is an illness, an (albeit it regularised) hysterical symptom. The only characters in the film who are not outwardly traumatised in this way are Jung’s wife and, ironically enough, Freud. But we see that behind the pragmatic façade of the founder of the psychoanalytic movement there lies a complex set of (indeed) Oedipal anxieties brought to the fore in his conflict with Jung, most clearly during the 1912 meeting of the International Psychoanalytic Association at Munich where Freud goes into a faint (the symbolic castration of the method’s father). Emma Jung, meanwhile, with her impeccable self-control and outward appearance of “normality” is perhaps the most blatant figure of perversion in the film; less a character than a caricature – anaemic, bloodless, as if all life had been drained from her and she is simply going through the motions of being human, like an automaton or a well-mannered zombie without need of special effects.

In making this film in this way (his third collaboration with actor Viggo Mortensen, all of them in the naturalist style), Cronenberg seems to be posing a question: Is cinema a psychoanalysis? Or, as in Videodrome and eXistenZ, is it the symptom? Or even the illness? Is cinema the representation of a collective desire which is otherwise unable to formulate itself? Or is it part of the repressive apparatus by which desire is normalised? And the question to which we will return again and again: Is a critical cinema possible – a cinema that is capable of exploiting the illusionistic character of the medium in order to disillusion? And if so, what would that mean?

Terry Gilliam, Brazil (1985)

5. If Badiou regards the work of Cronenberg as a philosophical machine exploring (or posing) violent enigmas, for Žižek the question is of the ontological character of cinema itself, moving from the experience of fantasy as a symptom of the real, or as a support of reality, to the real-as-symptom. This is a question Žižek frequently poses with reference to the work of David Lynch and also Terry Gilliam, whose 1985 masterpiece, Brazil (co-written with Tom Stoppard), is a kind of fulcrum between Eraserhead (1977) and eXistenZ. In Brazil, Žižek argues, Gilliam depicts “in a disgustingly funny way, a totalitarian society” in which the film’s hero “finds an ambiguous point of escape from everyday reality in his dream.” But this escape, Žižek insists, is not one from a true world into a false world, but the contrary, since the totalitarian reality in which Jonathan Pryce’s character (Sam Lowry) is trapped is constructed as a type of bureaucratic illusion. Moreover, “it is only in the dream,” as Lacan also tells us, “that we come close to the real awakening – that is, to the Real of our desire.”

Here, then, is the distinction between the film’s depiction of a totalitarian image-machine, and the implied totalitarianism of depiction as such: the image that always maintains a “subject-in-suspense-of-the-real,” so to speak.

At the other end of the Gilliam spectrum is his 2005 film Tideland, quite possibly the director’s strangest film – probably because it also represents his most sustained engagement with realism. There are no time-travelling dwarfs or viral catastrophes, no grotesque totalitarian bureaucracies, Jabberwockies or Baron Munchausens. The whole drama revolves around the localised imagination of a young girl played out against a landscape of southern US gothic. The weirdness of this landscape and the imagination that shapes it is so potent as film to the extent that it avoids the contrivance of depiction. The weirdness of Tideland is, so to speak, genuinely weird.

Based on Mitch Cullin’s novel of the same name, the third of a Texas trilogy, the film is “about” a pre-adolescent girl (Jeliza-Rose) who spends a summer at an isolated, run-down Texas farmhouse, with only a collection of dolls’ heads for company. The story is in part an examination of the way we use narratives as psychological defence mechanisms: how the fantasy of the “real” segues into the fantasy of the “imaginary.” While the storyline plots an arc of ever-increasing irrationality, this irrationality always somehow remains a reasonable response to the nature of the reality confronted by the characters in the film. Very near the beginning of the film, Jeliza-Rose’s father, Noah (Jeff Bridges), dies of a heroin overdose. Jeliza-Rose treats this as an ordinary state of affairs, he is, after all, a junkie and spends much of his time unconscious. This sets off a series of logical inferences that give much of what follows in the film an almost syllogistic necessity – one thing leads reasonably to another, right up to the taxidermy scene, when Noah is embalmed by their neighbours, and the blowing up of the local nighttrain, the “Monster Shark,” by Dickens, a mentally-retarded man-child with whom Jeliza-Rose embarks on a doomed romance.

Tideland is also Gilliam’s most controversial film. Despite winning the jury prize at the San Sebastian Film Festival, it was widely savaged by critics. Entertainment Weeklycalled it “gruesomely awful.” New York Times critic Anthony Scott described it as “creepy, exploitative, and self-indulgent.” Rotten Tomatoes gave it a critics rating of 4/10, billing it as “disturbing, and mostly unwatchable,” while in contrast noting a 60% audience approval rating. For his part, Cronenberg hailed Tideland as a “poetic horror film” – a quote used to market the film during its theatrical release. Gilliam himself has said he conceived of Tideland as a combination of Alice in Wonderland and Psycho, attracting the response from one critic that Gilliam is a type of diseased Lewis Carroll. The fairy tale element in Tideland, however, is stripped of the fantastical dimensions that characterised Gilliam’s previous film, The Brothers Grimm (also 2005): in returning to low-budget production with Tideland, Gilliam also moved away from the use of special effects as plot-motivation, allowing the tension between fairytale motif and unembellished realism to create a pervasive sense of unease which, in other films, would simply become entertainment.

Dennis Hopper as Frank & Isabella Rossallini as Dorothy Valens: David Lynch, Blue Velvet (1996)

6. Somewhere between Tideland and Brazil lies the axis along which David Lynch has pursued the principle concerns of his film-making from Blue Velvet (1996) onwards. For Lynch, the tension between fairytale motif and unembellished realism most often takes the form of a kind of film noir metaphysics. The “violent enigma” is pared back to a realism that collapses into itself, exposing the armature of its own illusion. This is a structural, not a moral, armature: whatever moral is on offer in Lynch’s films is simply one more element of the illusion itself. No hay banda. Lynch explores this tension regularly in the form of a dialectic of symptom and desire which achieves a kind of apotheosis in films like Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholand Drive (2001) – “a dialectics of overtaking ourselves towards the future,” as Žižek says, “and simultaneously retroactive modification of the past – dialectics by which the error is internal to the truth.” There is, to paraphrase an almost invariably misconstrued statement, no outside of the image.

Blue Velvet, David Lynch’s savage portrait of middle-American gothic, elicited mixed responses from critics following Dune’s box office failure two years previously, but nevertheless earned Lynch his second Academy Award nomination for best director.

Earlier work, Eraserhead and The Elephant Man (1980), both shot in black and white, had established the director’s credentials as both an experimentalist and an historical realist. While Elephant Man had garnered Lynch eight Academy Award nominations, Blue Velvet marked an apparent departure for Lynch into new territory as a film-maker, characterised by saturated colour, neo-noir atmospherics and surreal plotlines – elements that achieve a particular formalisation in later films like Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive. Blue Velvet is also the beginning of Lynch’s exploration of “parallel” worlds as both a recurring motif and as a structural logic. Here, the parallel worlds are those of middle-American suburbia (represented by Kyle MacLachlan’s and Laura Dern’s characters, Jeffrey Beaumont and Sandy Williams) and its toxic crime-ridden and violent underside (represented by the character played by Hopper, Frank Booth, a psychotic gangster; and the torch-singer Dorothy Valens, played by Isabella Rossallini, whose signature piece, Wayne and Morris’s “Blue Velvet” (1950), had earlier featured in Kenneth Anger’s 1963 film Scorpio Rising, a portrait of fetishised masculinity).

The film is all about taboo and transgression and a kind of collective unconscious of middle-class white America, situated in a 1970s still mired in the cultural fantasies of previous decades. Lynch beautifully satirises a whole array of nostalgias and sentimentalities in the process of exposing the libidinous forces driving the mass fantasy – whose lineaments increasingly resemble a neurotic overcoding of the “real” as the film proceeds towards its climax. These are subjects Lynch comes to revisit extensively in his next two films, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) and (the second half of) Lost Highway. Considered both a “prequel” and “sequel” to the Twin Peaks TV series created by Lynch and Mark Frost in 1990, Fire Walk with Me is an elliptical amalgam of clues and subterfuges about the last seven days in the life of Laura Palmer, whose death sets in motion the action of the TV series and constitutes – in the manner of a typical Lynchian motif – its central, unresolved “enigma.” Here Lynch explores a fragmentary and at times “hysterical” stylistic, anticipating the middle “Silencio” sequence in Mulholland Drive and establishing a template for the mood and overall construction of Inland Empire. Kyle MacLachlan (Blue Velvet), re-appears here as FBI special agent Dale Cooper, with Sheryl Lee as Laura Palmer playing a type of counterpoint role to Laura Dern’s Sandy Williams character: exposing the sexual underside of the white-bread suburban middle class depicted in the earlier film.

Lynch’s “red curtain” motif appears here perhaps for the first time, affecting a sense of thematic déjà vu between Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive which is also reinforced by the sequence with the “Man from Another Place,” echoing the appearance in Mulholland Drive of the mysterious Mister Roque (both played by dwarf actor Michael J. Anderson). Where Mulholland Drive later explores parallel narratives and complimentary dream states, Fire Walk with Me (like Lost Highway) explores the idea of split or multiple personalities, so that the film’s overall dramatic arc might be regarded as an account of Laura Palmer’s fragmenting psyche. The film’s preoccupation with fantasy, dreams and non-rational “logics” centred around a core “mystery,” appears to “resolve” itself around a sublimated libidinal force. As in Blue Velvet, the obscene locus of this force turns out to be the father figure – an incestuous, murderous super-ego.

The “mystery man”: David Lynch, Lost Highway (1997)

7. Lost Highway continued Lynch’s exploration of psychoanalytic narrative structures begun in Blue Velvet. If Blue Velvet can be read as an Oedipal fantasy, Lost Highwayfocuses – to quote Žižek – upon the “enigma of feminine desire” as unobtainable object. Blue Velvet begins with a type of sublimated wish-fulfilment: the symbolic death of the father – in fact, the father’s “paralysis”: he suffers a stroke. But this paralysis is also a typical Freudian “symbolisation” of the erect phallus – the symbolic authority of the father – who has in effect been struck-down in the dream of the son. We need only look to the final scene of the film, with Jeffrey lying on a deckchair in his yard, daydreaming, to realise that the entire intervening drama has in fact taken place solely in his imagination. It is as if he’s simply awakening and continuing his “idyllic” guilt-free suburban existence – his father, who has miraculously recovered, is sharing a drink with the neighbours around a BBQ. His mother, aunt, girlfriend and girlfriend’s mother are all arranged in a type of ideal familial tableau, either on the sitting room couch or in the kitchen. A mechanical robin, symbolising a trite soap-operative brand of “love” perches on the windowsill with a bug in its beak. Like one of those bugs we see at the beginning of the film as the camera descends below ground into the “underworld” of Jeffrey’s unconscious.

The supposed triumph of sentiment over the “depth of the human soul” is clearly advertised. The middle American suburban fairytale gets its happy ending, just before the screen goes black.

If we accept this premise, we can easily understand Blue Velvet’s subplot, concerning Frank Booth (Denis Hopper) and Dorothy Valens, as a transposition of the family drama. Frank, with his tumescent, contorted face – induced by inhaling nitrous oxide – echoes the paralytic face of Jeffrey’s father. Frank is the tyrannical, obscene super-ego in this narrative, who must somehow be overcome. Dorothy, as the victim of Frank’s tyranny and sexual perversity, stands for the mother who must be saved. Jeffrey assumes the role of the gallant hero who wins the affections of the mother and kills the father, while gaining the adoration of the young girl, Sandy Williams, who remains a type of purified mother-surrogate.

The typical virgin-and-whore theme is obviously represented here – one that returns in the dualities of both Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive. Its impetus in the film perhaps stems from what Freud identifies as the exploded myth of the mother’s inviolability, when the son discovers his (sainted) mother to be also a sexual object and available, as it were, in a way that is not remarkably different from that of a prostitute. In fact, by assuming the authority of the father, the son will not even have to pay, and can arouse the true desire of the mother (being the submission to his desire) through an act of real or symbolic violence. He strikes her, and immediately she is aroused. In Jeffrey’s re-staging of Frank’s “rape” of Dorothy, it is notable that his efforts at tenderness are rebuked, providing an alibi for the sexual violence that follows – a violence that further demystifies the romance attached to the otherwise unobtainable object of his desire. What is also significant in this respect is Frank’s impotence – reduced to an infantile condition (“baby wants to fuck”), in which he cannot bear to be looked at. The entire narrative, of course, is driven by Jeffrey’s guilt arising from his Oedipal wish and the subsequent attempt to “resolve” this guilt and restore a type of equilibrium.

In Lost Highway, the fantastical element of the narrative is organised around a type of “switch” – a device repeated in Mulholland Drive. The parallel story-lines of the film (Fred Madison/Renee and Pete Dayton/Alice) suggest a form of “repression,” whereby in place of a revealed “wish” (Fred’s desire to murder his wife) a second narrative is interposed, as the “symptom” masking this inadmissible wish (Pete’s love-affair with Alice). Mr Eddie (a.k.a. Dick Laurent), as a type of obscene super-ego, intervenes in this second narrative to force the issue and draw Pete towards a recognition of the “thing” he is unable to remember, the scene of some traumatic incident no-one around him is prepared to name (“The Real,” as Žižek says, “which resists symbolisation: the traumatic point which is always missed but nonetheless always returns although we try… to neutralise it, to integrate it”). The climax of the film comes with Fred’s execution-style murder of Mr Eddie/Dick Laurent and his pursuit by the police (both of which represent the instruments of super-egotic power in the film).

The first half of the film is set almost entirely in a functionalist, geometric Hollywood villa, whose super-rational architecture is deranged by the camera into Chinese boxes of enfolded chiaroscuro and involuted P.O.V. Renee, Fred’s wife (Patricia Arquette), a brunette costumed solely in black, performs her role in an inert, non-reactive way: Fred (Bill Pullman), a sax player, is shown restlessly moving through their geometric labyrinth smoking, watching the street through the window, listening at the intercom. Their domestic non-drama is disturbed by the appearance of a series of video tapes, which in successive stages document the outside, then inside of their house, progressing towards their bedroom, culminating in the scene of Renee’s murder with Fred kneeling on the floor covered in blood surrounded by a dismembered mannequin. The scene echoes an earlier one of Fred blowing a sax solo under strobing stagelights (his performance compared by Žižek to a kind of embodied tumescence) and anticipates Fred’s “migraine” in prison when, under a flickering cell light, his head appears literally to split open and ejaculate the mirrorworld narrative of Pete Dayton.

Symptomatically, Fred and Renee’s one effort at sex exposes Fred’s impotence. In his fantasmatic reincarnation as “Pete Dayton,” twenty-something autoworker, “Fred” (re-) encounters his (“dead”) wife in the form of her “double” (or ghost; she appears throughout in white): Alice, a blond porn actress and mistress to mob-boss Laurent who, however, immediately makes herself available to Pete’s inflamed longings. Pete is virile yet partially paralysed (in one leg, which is symbolically rigid the entire time he is in front of the camera – just as the camera, so to speak, is paralysed whenever continuity breaks down). Alice’s white to Renee’s black resolves into a second transitional scene set in the desert, where Alice, naked in the headlights of Pete/Fred’s car, flares into an “overexposed” image of unattainable desire (“you’ll never have me”) and is immediately substituted by the man with the video camera (“The Mystery Man,” the film’s superego).

In the first narrative, Fred suspects Renee of conducting an affair with “phallic” father-figure Laurent; this both arouses Fred’s desire to possess her sexually and sublimates this desire in an unconscious wish for her death. In the second narrative the relationship to Laurent is reversed. But this fantasy reversal is equally ineffective: Pete turns back into Fred at precisely the point when Alice tells him he’ll never have her. As in Mulholland Drive, Lynch employs a catalyst figure – in Lost Highway it’s “The Mystery Man” – who represents a type of perturbation at the level of Fred’s consciousness, communicating to him the fact of his repressed desires. That the Mystery Man does so in the form of video images, a mobile phone, and a video camera implies the degree to which desire is always already narrativised, so to speak, even when it can’t be represented as such – something to which Lynch’s film-making appears to address itself more and more.

Laura Harring becomes “Rita”: David Lynch, Mulholland Drive (2001)

8. Described as a neo-noir, Mulholland Drive continues Lynch’s exploration of the dialectical structure exploited to such effect in Lost Highway. Although its somewhat “schematic” quality is usually attributed to the first half of the film having begun life as a TV pilot – intended to be the opening instalment of a series – the mirroring effect of the first and second halves of the film is consistent with Lynch’s previous examination of psychoanalytic logics. In Mulholand Drive, the split between the film’s two halves suggests a “split” in the constitution of the film’s “subject”: the agent of protagonist Betty Elm (Naomi Watt) whose conscious life is riven by conflicting and disturbed motivations (most of them nonetheless trite). The dramatic form of the film reflects the tensions between desire and its sublimation, or the wish and its fulfilment.

In Mulholand Drive this takes the classic form of the suicidal fantasy, referring to the suicide’s desire to provoke the sympathy or distress of a loved one by virtue of her (“tragic”) death. In Mulholand Drive, the drama hinges upon the discovery of Betty Elm’s/Diane Selwyn’s dead body in a semidetached bungalow complex and the emotional response produced by this in the amnesiac Laura Harring character, “Rita” (named for a poster of Rita Hayworth she sees hanging on a bathroom wall). At which point, we shift from Betty’s fantasy to a retrospective unveiling of her inhabited “reality.” In this reality, all of the elements active within her fantasy appear to be reversed. The logic behind this reversal finds its focus in the “missing” causality – which is Betty’s suicidal wish (to become Rita), symbolised by the empty blue box and the blue key with which it is unlocked.

The film is set in and around Hollywood, with a focus on the film industry – or “dream factory,” as it’s called – as the ultimate form of “wish-fulfilment.” Betty arrives in Hollywood from a kitsch netherworld of middleclass suburbia reminiscent of Blue Velvet. Her film aspirations are immediately met, but are displaced by the mysterious appearance of Laura Harring’s amnesiac “Rita” – the escaped victim of an attempted “contract hit” on Mulholland Dr. In the parallel narrative, “Rita” becomes Camilla Rhodes, a successful actress who is having an affair with director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), while Betty (now “Diane Selwyn”) is an unsuccessful aspiring actress involved in a lesbian relationship with Camilla. Out of jealousy, Diane hires a hitman to murder Camilla – the appearance in her apartment of the blue key is the sign that Camilla has been murdered, following which Diane commits suicide. Diane’s/Betty’s fantasy is doubled, like everything else in the film, so that guilt and desire become inter-changeable; the death-wish substitutes for the wish for the death of the loved one, and so on, in a narcissistic spiral. The whole symbolic drama of substitutions, however, comes to rest within the confines of the “blue box” that falls out of Rita’s handbag following the “Silencio” episode and which Betty opens with a strangely geometric blue key: the box is empty, a kind of black hole into which the camera is sucked, precipitating the film’s narrative inversion. The key thus presents itself both as the key to an enigma and the key to nothing, to the entropy behind the image, to the featureless non-place of the Real.

While Inland Empire comes chronologically after Mulholland Drive, in many respects it follows more immediately from Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me – with which it shares a highly elusive and complex sense of structure, as well as a certain propensity for hysteria. (Grace Zabriski, who appeared in Twin Peaks as the mother of Laura Palmer here returns as the mysterious visitor in the opening scenes of the film, along with Blue Velvet lead Laura Dern.) However, with Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire shares the device of the “film within a film” (in this instance, a film called On High in Blue Tomorrows, which is itself a “remake” of an old German movie called 47, and for which Laura Dern’s Nikki Grace/Sue Blue character is about to audition at the start of the film). The film itself was largely shot and set between the Hollywood of Mulholland Drive and Łodz, in Poland, involving a “Polish” sub-plot (seemingly from the film 47 and set in the 1930s), along with a contemporary TV soap opera involving a rabbit family and “the longest-running radio play in history,” Axxon N – which together with the “film within a film” all begin to intersect at a certain point.

As in Blue Velvet, the film’s ending suggests that the entire intervening drama has taken place in the main protagonist, Laura Dern’s, imagination. The final scene shows her sitting with Grace Zabriski in the same situation in which the film began. Like Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, there is a sense of migration through or between different levels of subjective fantasy – whose locus is a sublimated trauma located somewhere in the past of Dern’s character, and which in one scene she apparently “confesses” to a Rabbi: a trauma which has to do, as in Twin Peaks, with childhood sexual abuse. Themes of imprisonment, murder and prostitution proliferate in parallel with a descent through the sexualised glamour of the Hollywood dream factory into a seedy underworld of libidinalised violence. As in so much of Lynch’s work, there is a prevailing sense of psychic dis-equilibrium, of the invasion of so-called “normality” by ever-prevalent and barely disguised forces of madness.

*Presented as a series of lectures, “Film & Critical Culture,” Philosophy Faculty, Charles University, Prague, October 2013 – January 2014.

Louis Armand is the Director of the Centre for Critical & Cultural Theory at Charles University, Prague. His books include The Organ-Grinder’s Monkey (2013) and the novel Breakfast at Midnight (2011) described by 3:AM magazine’s Richard Marshall as “a perfect modern noir”.

Leave a comment